The Architect

Issue 56 / Fri 19th Oct, 2018

We catch up with Alastair Beckett, bike designer extraordinaire, and responsible for some of the most successful bikes on the race circuit. Alistair talks about bike design, the rise of the high pivot bike and what the future may hold for mountain bikes.

Ali Beckett has been around bikes for a long time, helping design some of the most successful bikes on the planet. In a rapidly changing world, I caught up with him to chat about where bike design is heading and why everyone is getting excited about those high pivot bikes. We get a rare chance to take a glimpse inside the mind of one of the most in-demand mountain bike product designers and engineers out there.

Ali, you're a well-respected and accomplished designer, how did you get your first break into the bike industry?

I studied mechanical engineering in college I wasn't overly academic then I found engineering and that interested me; I'd always had a desire to tweak and learn about how things go together. I studied there for about four years, and it was my first experience with CAD, software and being able to design elements on a screen and I thought that was cool.

I rushed through my projects and brought all my bike parts in, and I would redesign my bike parts or just copy them and measure them up and try and model them. That accelerated massively my learning of the software side of things. When I finished the four years there, that's when I first went across to work at Chain Reaction because in this country if you wanted to work with bikes there was no other option and at that time it was relatively small.

I worked in sales and answering technical calls and that sort of stuff and quickly moved across to run the warranty dept, it was just me running it. I dabbled in the workshop building up my knowledge of mechanics, and engineering then got fed up and wanted to go and spend a season in Morzine. A couple of weeks before Ben Reid asked if he would help him at some World Cup races as a mechanic and I decided I would give it a go. I didn't earn any money for the first two years but gained plenty of valuable life experience!

What was your first design job in the mountain bike world?

A job at CRC came up, they were looking to increase the house brand team, so I went and helped them in the offseason. This was working on Nukeproof, and they were just launching Vitus at that point and had Ragley and a whole pile of things. It was a great opportunity, and I became the brand manager for Nukeproof. I learnt the hard way about how to deal with Taiwan and Asia, the process of getting stuff made.

I was in a unique situation because I was doing every aspect of it, I was doing the market research, coming up with what I thought the products should be, what the geometry should be, the travel should be, where’s the competition. Then I'd sit down and design it all with the help of Dale McMullen. He's a great engineer and great guy; he has a good eye for detail (he developed the original Mega with Brant Richards).

I was involved in the full range for 2015, the new DH bike, a new Mega, the slopestyle and dirt jump bikes. For some reason, we did them all in one go which was a baptism of fire. Needless to say, everything was late, and it was a real mission. I remember waiting on the frames arriving, from Taiwan to go to Eurobike, these were the first prototypes, and all the other guys were on holiday, and I was the only one in the office waiting for these frames to arrive and try and build five bikes and drive them to Eurobike. But I loved it. I always knew I wanted to work for myself, even when I eventually left (on good terms) I wasn't entirely sure what I was going to do.

The Mega is one of the most successful enduro bikes of all time. How does that feel to have been an integral part of that process?

I think it's cool, I get obsessed with details, and there are lots of bits I would chop and change. One of the biggest challenges designing the bike was being the product manager and trying to get the bike delivered on time and get all the spec sorted with the third parties and all those guys. That is an extremely difficult process to do so I was really, really pleased. To design a new full carbon bike and have it in stock the Monday after Sam Hill won the overall EWS series on Sunday. That was an achievement! I was really stoked and pleased with how that went.

Is there a style of bike that people or brands want designing for them? How does a product designer work with a brand?

Some brands know exactly what they want, know exactly how it's going to be and what they need help with is 'how should we get them made?' or ' what can we expect from the process?' Some clients need me to tell them what type of bike we should be making, should it be four-bar Horst link? High pivot? It's all about knowing what the customer wants.

Is it a UK customer? Or someone in the states that don't need the same mud clearance? Or is it targetting the more entry-level side of things? All of those things equate to how likely they are to be successful. These things all factor into what makes a good bike for that customer. There are so many different styles out there, suspension layouts, different sized bearings, clearances, all of that makes the product.

That is product design to me, not just sticking tubes together, it's understanding how it's going to be applied and who it is you're directing the product at. I could just replicate previous bikes for clients, but I want to do better. I don't think there is one bike design that is better than the rest, all of them work.

Are bikes starting to look the same? Is there a convergence point where all bikes essentially look the same?

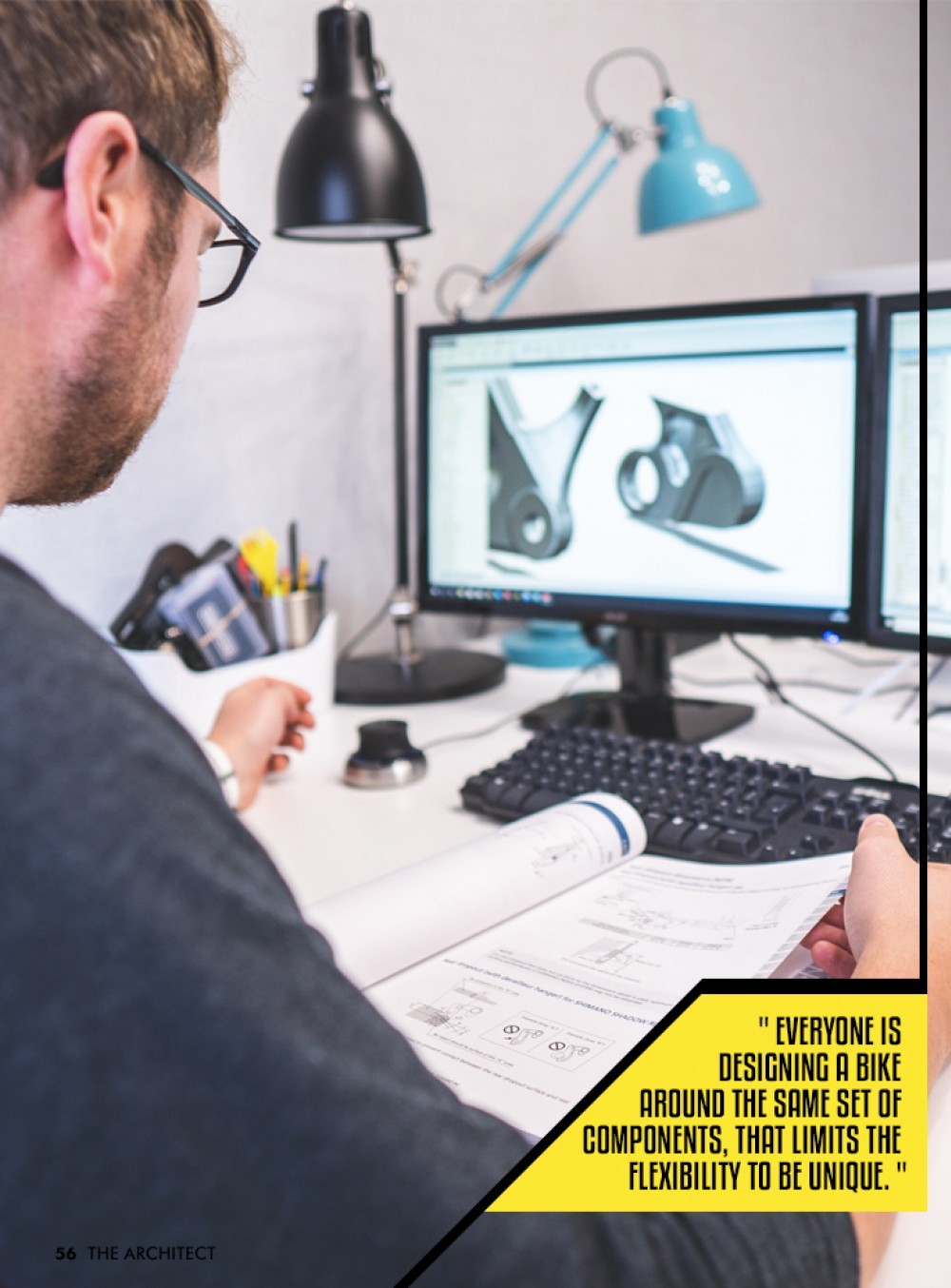

I do think bikes are starting to look similar and it's tricky. The easiest bike to make is a four bar style, that is the easiest bike to engineer. That's because a bike's a bike, it has to fit two wheels, and has to fit a drivetrain that comes on a certain specification. You know the drivetrain requires 'x' amount of clearance etc. Everyone is designing a bike around the same set of components, that limits the flexibility to be unique.

You have to fit around certain length shocks and standard bearing sizes, so the easiest way to do that, from purely laying out tubes and the welds just seems to be that four-bar layout. A vertical shock where you can bolt it onto the bottom bracket and easily position the main pivot is, from an engineering point of view, easier than putting a shock mount on a tube where you're trying to save weight or add flex.

The number of privately owned and truly unique companies, there aren't many of them now. These are the guys who have the opportunity to be unique and try something new. That's a risk, going away from the norm and what's commonly accepted.

Bikes are getting more similar, but I'm not saying that's a bad thing, as it allows the company to make improvements and make a better product for the customer. If customers want something unique, then it won't benefit them. The power of the brand comes into play and how they market themselves.

You're working on a high pivot bike with Forbidden currently, what's the buzz about high pivot bikes at the moment? Commencal have taken the world cup by storm this year on their Supreme with a high pivot downhill bike is it the future?

Yes, I started working with Forbidden right after I left my role at Nukeproof. The design was already done by Owen Pemberton who I met many years ago while working as a mechanic, and he was looking for some help to bring his design to market, and that’s where I have been offering some assistance. The High Pivot thing was all new to me this time last year, however, Owen was able to really help me to understand the benefits that it can offer, and although it might not be for everyone, it really appealed to me and I felt it offered something that the market was really looking for.

I can't say too much at this time as the product hasn’t been officially launched yet, but I think the results that everyone witnessed with the Commencal bikes in this year's World Cup DH series are hard to ignore. (albeit the riders on board definitely played a huge part in those victories without a doubt). High pivots aren't new, they've been around a long time. However it’s these smaller companies that are free from the commercial pressure that others might have, who are able to really delve into the detail and take a fresh approach to the design. Seeing it without clouded judgement if you will.

I don't think high pivots will be right for everyone, it will take time for them to become accepted in the mainstream market, but I believe they provide a viable alternative for those customers who are searching for something a little special.

The benefit of a high pivot is that, within reason, it allows the back wheel to move backwards and upwards, out of the way of a bump, essentially making the bike more efficient and handle rough terrain better. That's it in a nutshell. That's why it's been applied most effectively in DH bikes, as it is purely about bump absorption, and shouldn't be worrying about pedalling as much. That's why it's been easier to apply to a downhill bike up till now. The reason it hasn't been applied to shorter travel bikes so far is that in the past we have obviously had multiple chainrings, and you couldn't do that because you have to run an idler with it. Now with the adoption of one by drivetrains, that's one less barrier to the whole thing.

And the idler pulley is there because of chain growth?

If the idler weren't there, the pedals would kick back so much in suspension compression, so it, unfortunately, has to be there. Now, we are seeing lots of people experimenting with idler pulleys on their bikes. If you move the pivot too far away from the chainring, you do have to run an idler pulley. This is probably the biggest stigma, I never wanted a bike with an idler, something else to go wrong, another place to collect mud. I'm now at a point where I think the benefits outweigh that compromise.

So what are those benefits to high pivot bikes?

Rearwards axles path and absorbs bumps like no other and it feels like you have more travel, and the by-product we didn't foresee in our designs, is to do with anti-squat. Traditionally when you pedal on a bike, the suspension wants to compress, and your weight comes back. With a higher pivot, it's actually counteracting that so the bike ends up pedalling much better than a four-bar bike of the same travel. It blew our minds, we weren't expecting that. You can also run such a short chainstay length due to the pivot location.

As a designer, how important is the balance between form and function? Do bikes have to look nice?

First of all, when I design, the function takes the lead, so you have to make a list of priorities of what you want. Do you want a water bottle? What tyre clearance do you need? What size Shock do you want? All these questions need gathered up and put into a skeleton with the geometry and then that leaves you with quite a limited space for you to then design the profile or the aesthetics.

When I designed at Nukeproof for example, aesthetics was a big thing for me, I'd been working as a mechanic and seen all these top-end race bikes being raced, and I felt I had a good idea for what looks good and what didn't look good. When I look at bikes whose top tube lines up with nothing, and engineering and industrial design has been used to design a bike I feel like they've missed it a bit.

I don't believe we are designing a product here that you can't blend form and function together, you'd be hard pushed not to do that. Now that front derailleurs are a thing of the past, all these things are making it easier. As we move towards wireless drivetrains and stuff, you think, they're getting rid of all the complexity. Surely the job should be for the frame designers to adopt the same ethos and make something that's really great design with an eye for aesthetics.

Who does it well? Are there any examples you'd be willing to share?

I think Canyon do it well now, their latest versions look really good. I really like the new Specialized eBike, and you know, YTs look unique and flow well, I think they're all aesthetically pleasing. Bikes should look aggressive, and they should look dynamic. Marin is one of the great comebacks, some of their bikes are killing it, and the new 29er is pretty simple but it aesthetically pleasing and looks good.

Modern geometry is obviously a battleground. Are you enjoying the flexibility that modern trends allow in the design process?

I'm enjoying researching and looking into the geometry trends. When I started on my own, I spent a lot of time looking into it in depth and testing as much stuff as I could. I spend a lot of time looking into fork offset, as no one had explained it to me in a way that I thought made sense. So I went off and worked it out myself and came up with my own theories about fork offset and head angles.

I think there are guys pushing geometry for the sake of being different and there is always going to be limitations at the top and bottom of anything. Working and advising clients on geometry it's about establishing what they want for their bike, and making numbers that make sense and I think there is a sweet spot and I think people are going too far. I feel it really does depend on the application as well, are you creating a race bike, or for people that watch racing and then ride trail centres, they are two very different things.

Have we got sizing on bikes right, shouldn't we be measuring bikes in a different way? For instance from pedals to grips?

I hundred per cent agree with that. I think that it's tricky as there are so many elements to geometry. One of the things we haven't talked about is designing frames where every size has a different rear-centre length (chainstay). From an engineering and manufacture point of view, it's very difficult to do, and the factories don't like it, but I think that feet-to-bars measurements are key.

That's how Sam Hill measures his bike, he gets on any bike, no point telling him any numbers, he just gets a tape measure out and measures feet to bars, and if it makes sense, then he's happy, and away he goes. I do think that's the only true measurement you can work off.

It's trial and error for a lot of people as well, such as how much stack height can affect things. Stack height can make a big difference to the reach of a bike. On extra large sizes, with slack head angles, by the time they've got the bar height up, the reach is often reduced. Then I looked into back-sweep on handlebars, where one degree could put your handles 15mm back! At the same time, numbers on a website, are one thing, it gets you reasonably close, but there is still no replacement for swinging a leg over a bike and testing it.

What do you feel the future holds for bike design and development?

I think we're at a good place now. It feels there have been huge advancements in the last five years since enduro became a thing, but frames are still bolted together in the same rough layout. I can't see any big changes coming, just constant small improvements to things like bearing quality, or how bikes are silenced by mechanics on the downhill circuit.

I think it's the small details for now. I think we will see more small companies coming through, I keep comparing it to the craft beer industry, maybe people are prepared to spend a little more money on something that is unique. Riders always want something that no one else has!

Thanks to Ali Beckett, Redburn design

By Ewen Turner

Ewen Turner is a self-confessed bike geek from Kendal in the Lake District of England. He runs a coaching and guiding business up there and has a plethora of knowledge about bikes with an analytical approach to testing. His passion for bicycles is infectious, and he’s a ripper on the trails who prefers to fit his working life around his time on the bike.